Housing agency one of downtown’s biggest developers

By Jennifer Hiller/jhiller@express-news.net

Published: Sunday, December 12, 2010

Photos: Bob Owen

Not too long ago, vacant downtown property owned by the San Antonio Housing Authority seemed unimpressive: a few acres along a weedy ditch and another site that was a blighted, notorious public housing project.

That was then.

Today, SAHA finds itself in command of some properties that private developers would envy.

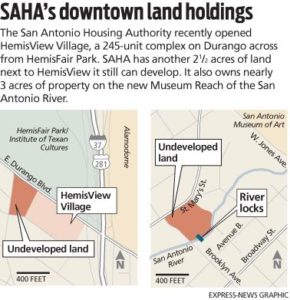

The largest chunks of remaining vacant land it holds are about 3 acres of River Walk property in the rejuvenated Museum Reach section and 2 1/2 acres on Durango across from HemisFair Park, with a view of the Tower of the Americas. These are suddenly prime sites that the city desperately wants redeveloped.

But even with a shortage of downtown rental units, SAHA’s role in building more downtown housing — particularly market-rate rentals — is not without debate.

Its core mission is building and maintaining affordable housing, and it serves about 65,000 adults and children — with a waiting list of thousands more. So the agency walks a fine line as it tries to mix up the socioeconomics of its properties by adding market-rate units downtown that compete with private businesses during a tough economy.

“When they put units on the ground, it’s like any other project,” developer Steve Yndo said. “They compete with your project.”

The agency has no solid plans or a timeline for what it will do with its remaining vacant urban sites.

However, given the slow economy and ongoing difficulty in securing construction financing for private projects, SAHA finds itself among the few downtown players positioned to move forward.

“Business leaders have told us they want to attract more jobs and people downtown,” said Lourdes Castro Ramirez, president and CEO of SAHA. “We’re at a point where we know we all have a role to play.”

Last week, SAHA belatedly celebrated the summer opening of HemisView Village, a mixed-income apartment complex that’s part of the Victoria Commons development — where the crime-ridden Victoria Courts public housing used to stand.

SAHA's HemisView Village is a mixed-income apartment complex that's part of the Victoria Commons development where the crime-ridden Victoria Courts public housing used to stand.

Of 245 apartments at HemisView, 12 are affordable units and 49 are public housing units.

The remaining 75 percent, or 184 units, are market rate, with rents between $741 and $1,264 and renters who don’t qualify for any sort of public subsidy.

Mayor Julián Castro wants the agency to keep building.

“As a public entity, SAHA in some ways is more nimble during a downturn,” Castro said. “SAHA’s primary mission is to create quality, affordable housing. While it’s doing that, it can serve as a powerful economic revitalization tool.”

Debating market rate

The biggest potential threat SAHA poses to private developers: It owns land outright, doesn’t pay taxes and receives government subsidies.

Meanwhile, developers struggle to get loans in the tight credit market.

Although high for San Antonio, downtown rents already border on the low side for developers to make a successful project, given the higher costs of working in urban areas. Many projects are on hold.

And thanks to changed mortgage-lending guidelines, some condo projects have switched to rentals, including one that Yndo helped develop, the St. Benedicts lofts.

With city and civic leaders pushing for thousands more downtown residents, developer David Adelman, partner at Cross & Co., said SAHA can help keep a diverse income mix downtown, which he believes makes for the best kind of neighborhood.

“We think the market is better served by more units,” he said. “I’m all for development if they can figure out how to get it going and done.”

But SAHA’s market-rate units make developers nervous.

SAHA’s approximate market-rate rent is a little more than $1 per square foot at HemisView, according to data compiled by Cross & Co.

Most other new, market-rate properties charge between about $1.30 and $1.50. The highest rents are at the Pearl Brewery, and average between $1.50 and $1.65.

“The problem is if they undercut rents,” Adelman said. “SAHA has to be careful not to use their advantage to suppress rents. It would establish the market at a rate below our ability to compete.”

On the other end of the spectrum, advocates for affordable housing don’t want to see SAHA sacrifice safe, work-force housing to add market-rate units.

Community activist and former City Councilwoman Patti Radle said she’s concerned that SAHA’s market-rate units are supplanting too many affordable apartments.

“It’s a real philosophical premise. Is San Antonio for everybody or is it for a certain sector?” Radle asked. “What happened with Victoria Courts did erase a lot of the affordable housing. (Downtown) is a very helpful location for people who are on low incomes. It makes the city more accessible.”

At the same time, Radle said she understands why SAHA wants to add some market-rate units to its projects.

“I don’t want to create poverty pockets,” she said. “I appreciate that and I think that’s important.”

Victoria Courts once had about 660 units. At the renamed Victoria Commons, where HemisView was built, another rental unit SAHA opened in 2004, Refugio Place, has 50 units of public housing, 55 of affordable housing and 105 at market rates.

Ramirez said SAHA never can meet the demand for housing, but wants residents to socialize across socioeconomic groups. Creating mixed-income communities avoids problems historically associated with isolated islands of public housing, she said.

Yndo said he doesn’t think SAHA has undercut the market so far, and the bigger issue for downtown redevelopment is attracting more high-quality jobs and small companies.

“The market is $1.30 to $1.35, which is hard to do anyway, but that’s San Antonio,” he said. “Unless we get quality jobs and people who are making $50,000 to $60,000 a year out of college or by their late 20s or early 30s, it’s going to be hard to build units.”

HemisView

Some say that even when SAHA does market-rate units, it’s not really in direct competition with private projects, which lately have offered amenities such as Pilates studios and sleek, industrial interior finishes with concrete floors, expansive windows and exposed ductwork.

HemisView does have amenities such as a pool, a secure parking garage and the like, but it’s not apples-to-apples with some of the luxury amenities at other communities.

“They don’t have all of the high-end amenities,” Yndo said.

Sandra Valadez moved into HemisView in July with her boyfriend after searching for rentals mostly in Alamo Heights.

At more than $1,200 a month, the rent was a stretch, but Valadez said they couldn’t resist the views. “We looked at each other and said, ‘This is out of our price range, but we’re going to do it.’ ”

Despite HemisView’s Tower views, Irby Hightower, principal at Alamo Architects, said SAHA probably won’t ever threaten other developers.

“They’re a public agency. It just doesn’t happen,” he said. “The hardest thing for SAHA to do is build real market-rate units with nice materials and expensive fixtures and so on.”

But SAHA can do projects that others can’t.

“No one else right now is really building,” Hightower said.

Because commercial financing depends heavily on what’s happening nearby and pioneering developments make lenders wary, SAHA’s downtown work could prove a viable market exists.

“A typical commercial developer can’t be first,” he said. “They’re not allowed to be first.”

River plans

SAHA’s river property occupies a prime position in River North, a light-industrial area the city wants to see turned into a mixed-use mecca with residential, retail and office space.

A master plan adopted last year looked at the 377-acre area along the refurbished 1 1/2-mile Museum Reach river segment as one of the best places to add more local people — not hotels — downtown.

Prior to the river face-lift, the gritty area largely was overlooked. SAHA in 1940 built the Rex Apartments at St. Mary’s and Brooklyn streets, backing up to the San Antonio River. Seniors lived in the 89-unit subsidized housing complex.

In the 1940s, SAHA built the Rex Apartments on the land that's now next to the locks and dam on the San Antonio River. When renovation proved too costly, the housing authority razed the complex in 1999.

In the late 1990s, SAHA tried to sell the aging property. Then it switched course and wanted to renovate, but that proved too costly, and the project was torn down in 1999.

Today, it has a direct view of the river’s new lock-and-dam system and is a short walk from the San Antonio Museum of Art and Municipal Auditorium.

Ramirez said the agency has “kicked around some ideas” about what to do there. “It’s prime property,” she said.

Ben Brewer, president of the Downtown Alliance, thinks the property could support between 200 and 300 housing units.

“They realize it’s one of the best locations on the river,” he said.

But Brewer is among those who would rather see SAHA sell the property for a fair price and use the proceeds to build on a different site.

Developer James Lifshutz, too, believes the property is simply too excellent.

“The site deserves a much higher-end residential product than SAHA has experience building,” Lifshutz said by e-mail. “Thus, in my opinion, they should sell that site and use the proceeds to further their mission elsewhere.”

Ramirez said SAHA hasn’t had any purchase offers in recent years, but emphasized that whatever it does with the land will happen with community involvement.

“We have no concrete plans,” Ramirez said. “We want to begin a very open, transparent process to determine what to do with that property.”

But before the river property, Ramirez said SAHA’s immediate goals include the construction of homes for first-time buyers at Victoria Commons and completing a plan to articulate what the agency wants in new developments.

It’s also using federal stimulus funds to renovate several aging facilities.

Then it will return to the river site.

“I think the Rex property is tied in with the whole River North area,” she said. “There are a lot of key players. We have to figure out what can be reasonably achieved in the next five years or the next 10 years.”

Potential plans

Immediately next to HemisView, SAHA has 21/2 vacant acres left to develop, which it has designated for commercial use.

The Lavaca Neighborhood Association wants a grocery store there, and that parcel will be considered during the master planning process for HemisFair, which recently started.

SAHA won’t necessarily have to follow the HemisFair plan, but Ramirez said the agency has met with the planners and wants to participate in the process.

It’s a different approach than the agency might have taken a few years ago.

Prior to the arrival of SAHA board Chairman Ramiro Cavazos and Ramirez, previous SAHA leaders had a turbulent relationship with residents and neighbors.

“I think the agency was more isolated,” Ramirez said. “We have a different approach now.”

That new attitude has left many optimistic, but cautious.

Yndo said he is in favor of good SAHA developments but that history shows that’s a struggle.

“The HemisView and Victoria Courts turned out real well, but it took the neighborhood and a lot of the architects who live in the neighborhood to hold their feet to the fire to make sure they did a quality job instead of a standard-issue suburban project,” Yndo said.

Seahn Lobb-Barrera, president emeritus of the Lavaca Neighborhood Association, said the success of HemisView — already 85 percent leased — and SAHA’s vastly improved community relationships have given him confidence in the agency’s ability to develop downtown.

“It’s like night and day, to put it quite frankly,” he said.

The new approach is this: “There is no ‘they,’” Lobb-Barrera said. “It’s ‘we.’ We’re their neighbors as much as they are our neighbors. It’s, ‘What do we want to do in our neighborhood?’”